It was lunchtime in Ernakulam; Fafa suggested going out for a meal with the family. My mother-in-law has been cooking a plethora of delicious Kerala cuisine — most I had never had before but would gladly include in my top ten most delicious meals of my life; he wanted her to take a break from the kitchen and enjoy a shared meal instead.

We didn’t know where we were going; only my father-in-law, who was directing the driver, had been to this place.

I turned my attention to the road. The abandoned school, the massive air tank, a fish lady resting in front of a relatively empty market and a row of butcher shops. I wondered whether there were butchers by the road in other parts of India or if this is more Kerala-specific.

Soon after, the car stopped for a few seconds.

Father-in-law’s first choice of restaurant was closed. “We will try another hotel,” he said, entering the car back. “Hotel?” I turned to Fafa. “Yeah, the restaurant”, he replied as if I had just overheard it wrongly.

I later found out that a hotel is what Indians call a restaurant.

After a few more turns and a few more butcher shops, the car went inside a crowded compound. “We have arrived”, father-in-law announced this time.

“Brothers” signage in red hung on the side of a house with a red brick roof. I followed him inside while Fafa followed with his mother at the back.

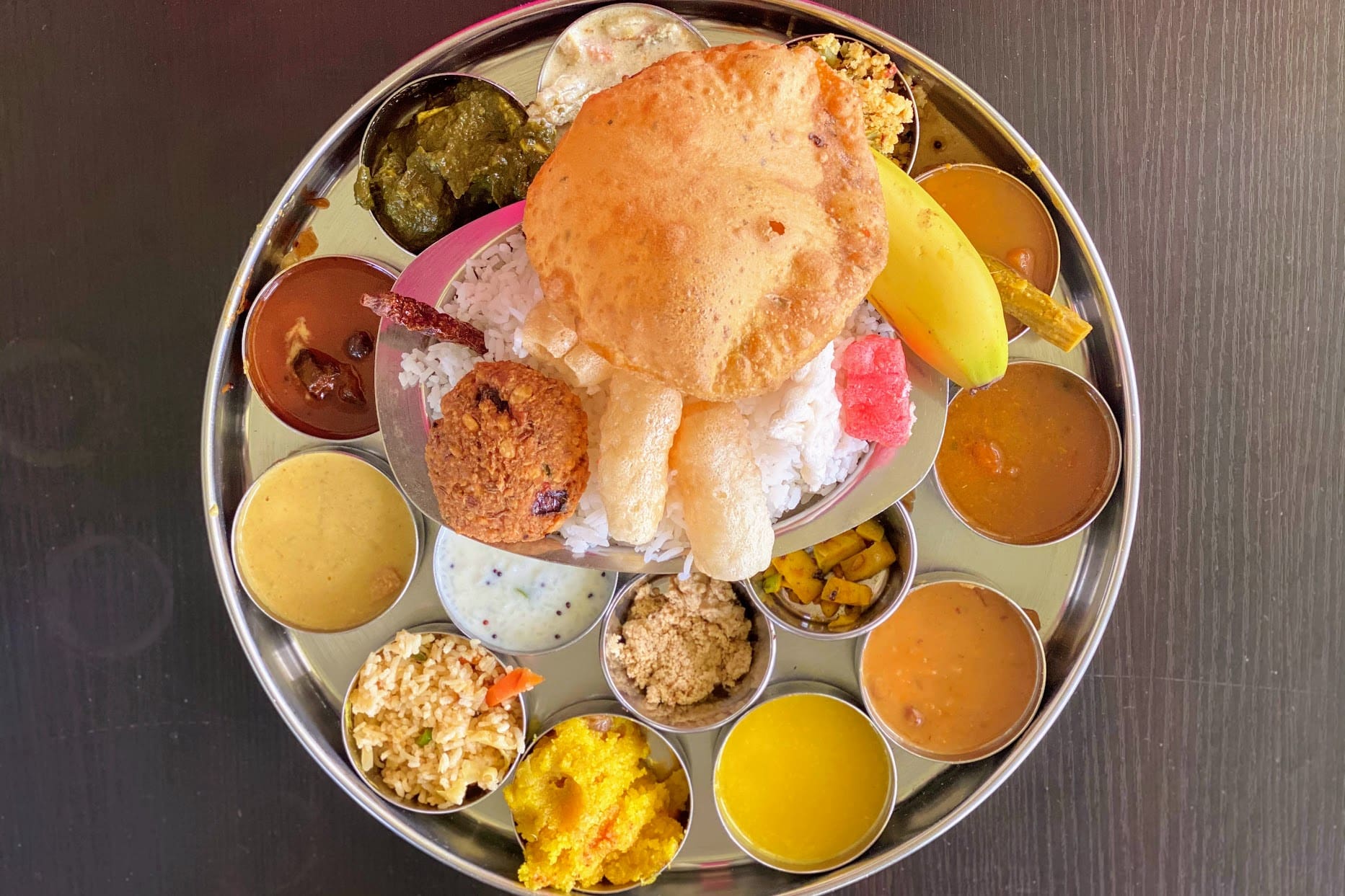

The 50 years old restaurant was packed, primarily by patrons who were eating as if they meant business.

There was not much to say about the restaurant’s interior, just rows and rows of wooden dining tables forming an alleyway for the people to sit and eat. The smell of the food was the only thing that could compete with the loud chatter of people talking, the steel dishes, and the wooden chairs being pulled. It was bewildering.

I can smell the spiciness mixed with the freshly fried fish and the sweat pouring from the heat. Finally, I was ready to be the patron who meant business.

The waiter came and directed us into a labyrinth of walls and sat us at a relatively empty, much more prominent table, which I assumed got something to do with what my father-in-law requested them earlier. So it looks like he has been before.

Below the fluorescent light, we sat.

“What do you want?“, my father-in-law asked me. “I will see the meen..” Even before I finished my sentence, the waiter started reciting the menu “Fish Poriyal, Meen Kudampuli, yada…yada…yada…” at a speed that would match the live sports commentator. He had no time for pleasantries nor to entertain the clueless looking me.

“So?” Fafa asked. “I am not sure. You choose for me” — a rare request from my side. He then said a few things in Malayalam, and the father-in-law confirmed a few more items and off went the waiter.

Then he came back, only seconds later, with a jug of water. The drinking water was pink. I was told it’s called Pathimugam (Indian redwood soaked in water). A Kerala thing, it supposedly has healing power. Boy, I was so intrigued.

Before the novelty of the pink wood-soaked water even wore off, our food came— rice with fish, sambar and some veggies. The fish and the sambar were piping hot; I scoped a piece of the fish and the sambar-soaked rice with my hand and ate it.

I so wanted to like it — I usually have the best meals in similarly styled eateries back in Indonesia. Unfortunately, though it had the same promising indications — unfriendly waiters, bare minimum effort, uninviting ambience, the food didn’t do it for me.

I didn’t like the rice (later, I learned I don’t like Indian rice), and the fish was just okay. However, I think my mother-in-law’s cooking spoiled me. “The other hotel is better,” my father-in-law suggested as if he could sense that it wasn’t a satisfying meal for me. I told him this was good, just that his wife’s cooking was better.

Without being prompted, the bill came soon after, handwritten on a piece indicating that: you have finished eating, so don’t dilly dally and make room for the new patrons. Order, eat, go – on repeat.

I beelined my father-in-law to wash hands at the back and then pay the bill to the owner sitting at the cashier desk—one of the brothers of the Hotel Brothers, I assumed.

I suppose it wasn’t a restaurant one tends to go to for an experience, but EXPERIENCE is what I got. Though the food might be the least favourite of all the food I had in Kerala, the experience made up for it. I have seen a scene in many South Indian movies but never got to experience — the authentic South Indian hotel/eatery food culture — until that day.

Follow me on Instagram@KultureKween for more recent updates.